As you’d guess from the spelling, “ceilidh” (kay-lee) is a Scots Gaelic word. Yet at the same time, some of the dances, like the Cumberland Square Eight, seem to be named after places in England, while others, like the Virginia Reel, seem to be named after places in America. Some dancers feel inspired to wear a kilt, others a sheriff badge.

So from whence does modern English ceilidh hail? Is it English, Scottish or American? The answer is basically: yes. Plus French. And a few others besides.

To explain, here’s a brief history:

English ceilidh – origins

Going back several centuries, country dancing was popular in England, as it was across Europe, amongst both aristocrats and commoners.

The different European styles influenced each other, with French court dances having a particularly big impact. That is why the names of many ceilidh moves are French words or corruptions of them e.g. promenade (walking fancy), and do-se-do, which came from dos-à-dos (back-to-back). Maybe the “yee-ha” some people like to shout as they do-se-do should really be an “ooh la la”.

The European colonials who went to North America took these dances with them, where they became further mixed together. They weren’t as known there as they were in Europe, so callers were introduced to explain them. Different styles developed, such as square dancing. Musicians blended British tunes with groovy, syncopated African rhythms that they picked up from the slaves.

Meanwhile, back in Blighty, England’s brutal industrialisation broke up many of its rural traditions. Scotland and Ireland’s fared better, as the people were more spread out, and they were less culturally dominant so had more nationalist interest in their folk cultures. Scottish “ceilidhs” and Irish “ceilis” thus stayed popular throughout the 18th and 19th centuries – they were social occasions involving dancing, music, stories or poetry readings. Robert Burns, the lauded 18th century Scottish poet, read his poetry at them.

English ceilidh in the 20th Century

In the 1950s England got back into folk dancing in a big way, but via a convoluted route. Because the country went mad for square dancing. Americana was in fashion after the war, and there were square dances in many hit American films like Gone with the Wind, My Darling Clementine and The War of the Worlds.

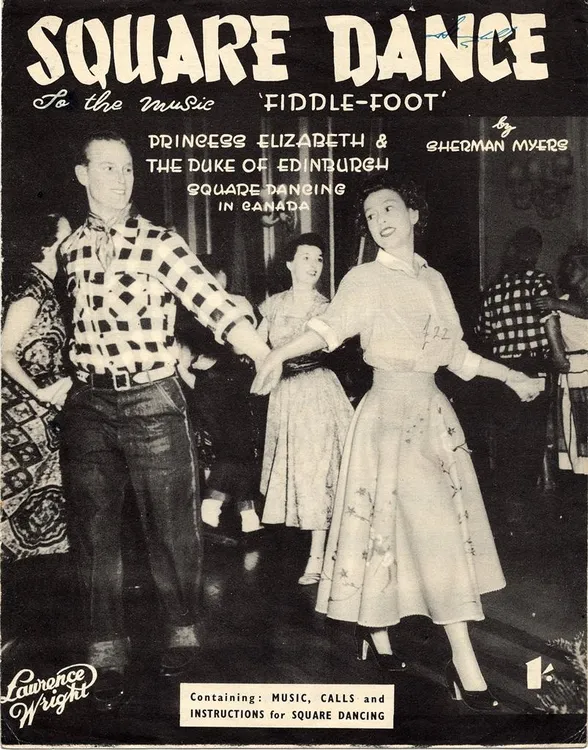

And so “barn dances” – so called as the films had shown the dances in or near barns, sprang up over England. Attendees came wearing checked shirts and cowboy hats. The press picked up on the craze and promoted it further with radio and TV programmes such as Happy Hoedown, and photos of then Princess Elizabeth, Prince Philip and Princess Margaret square dancing during a visit to Canada in 1951.

By the folk revival of the 1970s, the craze had quieted down. But younger English folkies who wanted to put on folk dances didn’t want to call them “barn dances” as those were still American themed. And the term “folk dancing” was associated with prim and proper middle aged types, and decidedly uncool. So they named them “ceilidhs” after the Scottish ones.

Despite the name, though, the 70s English ceilidhs differed from the Scottish ones. The bands played many slower tunes, thinking that the Scottish tended to be too hasty about it. And they kept some of the US-inspired features, such as the caller (they’re rarer in Scotland), since you need one in a country where the dances aren’t so well known.

Where we are now

The result of all this that the ceilidh dances popular in England today because they’re easy and fun are a somewhat mixed up bag of cultural influences.

That’s reflected in the names, although not always reliably: the Cumberland Square Eight, also known as the Cumberland Sausage Dance, does – shockingly, appear to be from Cumberland. But the Virginia Reel is a version of Sir Roger De Coverley, one of the last real country dances to be widely danced in Britain, which went to America and came back again.

Other dances were written more recently: The Flying Scotsman (the one about trains) in the 50s, the Oxo Reel (the one about stock cubes) in the 70s, The Muffin Man and Boston Tea Party in the 80s.

And for the music, Bellamira likes to do a mixture of tunes and songs – banging gallopy English ones, fast and furious Scottish ones, groovy American ones, slinky French ones, and our own that are influenced by all of the above. Hybrid vigour is a thing in nature – the first generation of two different animals, like a liger – a cross between a lion and a tiger, is mightier than either a lion or a tiger. And it’s also a thing in ceilidh.

***

This blogpost is by Josie. Most of the information in it comes from two sources:

&